A Five-Part Blog Series to Bust the Myths Surrounding VPN Intelligence Data

In this five-part blog series, we tackle the questions our customers ask us, with a goal of busting the myths that are driving those questions. In our first blog post of the series, we dispelled the myth that all VPN-driven data is the same. For Part Two, we addressed the myth that VPN breadth doesn’t matter.

In this blog post we take on the myth that corporate security and IT teams only need to worry about the ability to detect and screen the VPN services included in a Top Ten list they’ve found online. But as you’ll see, there are flaws to this strategy.

VPN usage continues its upward trajectory. Today nearly one in every three people worldwide use one, making VPNs one of the most popular pieces of consumer software. Among the biggest reasons people use VPNs are security (43%), streaming (26%), and privacy (12%).

As any IT professional knows, the increased popularity means increased risk. VPNs have been popular tools for cybercriminals, who use them to obfuscate their original location, circumvent firewall blocks or even deep packet inspection, among other things. Once a nefarious actor has breached a network through a compromised device, such as the work PC of a remote worker, the entire network is at risk. In January of this year, police in Europe shut down VPNLab, a VPN service that cybercriminals used to distribute malware and ransomware to over 100 businesses throughout the continent. These cybercriminals were able to avoid detection tools because the VPN encrypted the traffic to the endpoint.

For publishers, people using VPNs for streaming may often be circumventing digital rights management rules put in place to prevent piracy from siphoning off revenues. In fact, piracy is expected to skyrocket as inflation and subscription fatigue collide. Content owners and operators are fighting to protect intellectual property, and are finding that fighting piracy and protecting content assets is coming down to a cybersecurity issue within their organizations.

These are not idle concerns. Naturally, corporate security teams are keen to understand the VPN market better, including which services are favored by bad actors and which are more benign. It’s a topic we’re asked about frequently, and are happy to provide our clients with the insight and tools they need to make smart decisions regarding who can access their networks, who should be flagged for additional authentication, and who should be blocked altogether.

Myth #3: Covering the top Ten VPN sites provides sufficient protection.

Fact:

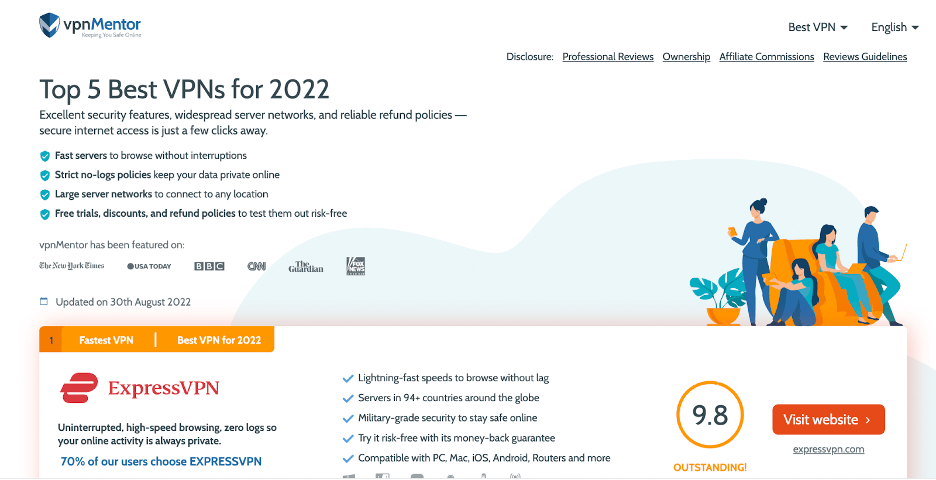

Google “Top Ten VPN sites” and you’ll get a plethora of results. In fact, Google returned 53 million results in less than one second. Some of the Top Ten lists are created by well known entities, such as Forbes, Security.org and CNET, while others, like Top10VPN.com, should raise alarm bells.

But even if the source is reputable, should you trust its analysis? Take the Forbes list, which analyzed VPNs for the key features that Forbes editors value, namely cost and number of servers worldwide. The top VPN selected, Private Internet Access, was chosen because it “strikes a perfect balance of pricing, features, and usability.” To their credit, Forbes notes that some security teams are uncomfortable with its “checkered past.”

We at Digital Element are uncomfortable with the whole notion of a Top Ten VPN list, and the advice it delivers. How many VPNs were analyzed to begin with? How were they selected? In the case of Forbes, that data is absent from its report.

In its The Best VPN of 2022 list, Security.org tells readers that its security experts analyzed “dozens” of VPNs, to determine which are the best. How many dozen? And why were they selected? If a VPN wasn’t analyzed, can we assume it’s safe? How should the security team treat traffic that comes through those unanalyzed VPNs?

This is the challenge with relying on Top Ten VPN lists. On the whole they are a meaningless metric for a variety of reasons, all of which are well worth exploring. For starters, there are way more than 10 VPN services in the world today. In fact, there are way more than dozens of services. There are literally thousands of existing services, with new entrances occurring daily. In such an environment, how can anyone claim which ones ought to be included in a list of Top Ten? From our take, the most popular VPNs in the Top Ten lists are affiliate links that pay the person promoting the VPN. You can see in this list, the commissions for a sale. There is quite a lot of money in it. It’s no wonder so many people promote them.

Second, some VPNs are more concerning to specific industries than others. If you’re a company that streams copyright-protected content to subscribers, the commercial VPNs are more relevant to you than corporate VPNs. Many of the VPNs boast the ability to circumvent digital rights access parameters, which is a direct threat to your business. Consequently, your list of Top Ten VPNs will be based on a different set of criteria than a global retailer’s.

Third, the lists themselves are very suspect. While there are thousands of VPN services, many are owned by the same set of parent companies. For instance, 105 separate VPN services are owned by just 24 companies. As it happens, the VPN parent companies also own the review sites, which means they’re essentially grading their own homework. Kape Technologies owns multiple VPN services, including ExpressVPN, CyberGhost, Private Internet Access, as well as a collection of VPN review sites. There is an obvious conflict of interest between owning a service and writing its review.

This is a significant issue in the VPN space. In fact, U.S. lawmakers recently asked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to examine the promises VPN service providers offer consumers, as a study revealed that 75% of them make exaggerated or outright false claims about the level of protection and privacy consumers can expect.

The Digital Element Difference

Digital Element has a policy to review and classify all new VPN services as they emerge. We also monitor more than ten — or even dozens of VPN services. Currently, we monitor 361 VPNs, 56 proxies, and two darknets, which we’ve identified through mapping out the entire provider network and identifying darknet nodes.

We go beyond determining if a service is a VPN or proxy, we also go to the source of where those VPNs exist. We also provide contextual information about the VPN provider itself, a feature that is unique to Digital Element.

For instance, we provide nearly 20 fields about the provider, ranging from ID, Provider, Site URL and whether it’s a paid or free service, to location and whether it accepts crypto payment.

The rich detail we provide allows security teams to establish best practices for VPN traffic. For instance, you may opt to ban all users who use a VPN that has no paper trail, accepts payment in crypto or located in a region of the world where you have no customers, offices or employees.

Next Up: VPN threat vectors originate from common sources and remain static. Or do they? We’ll dig deeper and report on what our proprietary technologies reveal.